Dare to wonder and make wonders?

Drop us a message.

For decades, the most chosen languages for low-level programming are C and C++; they offer great power but bring responsibility to the programmer.

Writing code in C++ became hard, so new languages were born - Go and Rust. Both target low-level operations tasks, operating systems, and cryptographic services, but they were born to produce efficient, performant, safe, and scalable code, also easy to use and learn.

Rust and Go remove the concern about the deallocation of memory and save the back of mistakes that lead to memory leaks or segmentation faults. That helps programmers to focus on business coding problems.

They have different memory management solutions. Go uses a garbage collector, while the Rust compiler has a borrow checker that saves the back and makes code memory safe.

This is the story about Rust, so we will get to look at how the borrow checker moves and manage values in memory. In effect, we will cover unique concepts which give Rust's speed, security, efficiency, and reliability, which makes it a good choice for developing new protocol solutions in the blockchain.

Knowing Rust allows us to keep up to date with cutting-edge technology and to understand better protocol solutions in development. More and more tools in the web3 world are being developed in Rust, which facilitates the development of a decentralized application. So knowing it allows us to write faster and safer code.

To fall in love with Rust, you need to understand two unique concepts - ownership and borrowing.

The developers must have a certain level of awareness about what happens in memory because, that way, we will have safer and more secure code.

Let’s compare:

To make ownership possible, one must follow three rules:

There are three approaches to what happens in memory when we assign one variable to another, the ways how variables and data interact:

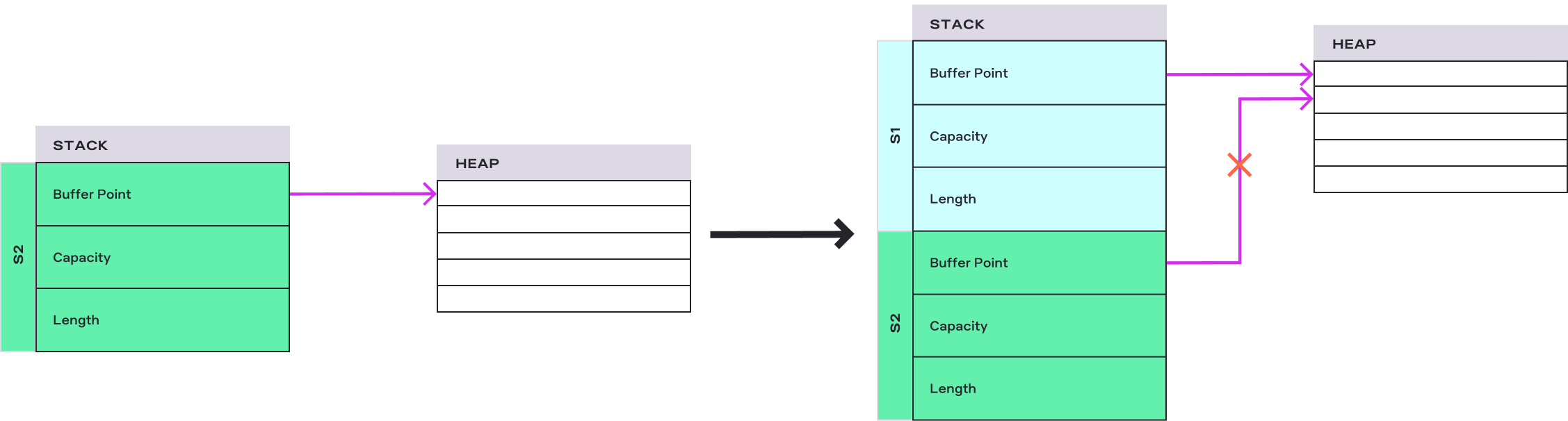

For the type whose size we don’t know at the compile time, and it can dynamically grow(i.e., Strings, Vectors), the memory is allocated on the heap, where on the stack, we have:

Example:

let s = String::from("3327");

let s1 = s;

println!("{}", s); //not okWhen we assign s to s1, the s moves to s1, the data stored on the stack are copied, the allocated buffer on the heap remains intact, and now the s1 is responsible for freeing the heap buffer. In Rust, the memory is automatically free when the variable that owns its value goes out of scope.

The above code will not compile as the change of ownership happens, and s is not valid anymore.

The memory is allocated on the stack for the type whose size we know at the compile time(i.e., integer, characters, Booleans).

Example:

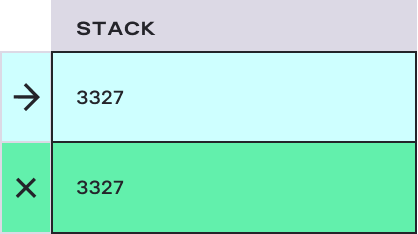

let x = 3327;

let y = x;

println!("{}", x);

When we assign x to y, it copies the value to the y and creates a new value on the stack.

All primitive types implement the Copy trait, and if struct and enum need to implement the Copy trait explicitly, all the types inside them need to implement the Copy trait.

Example:

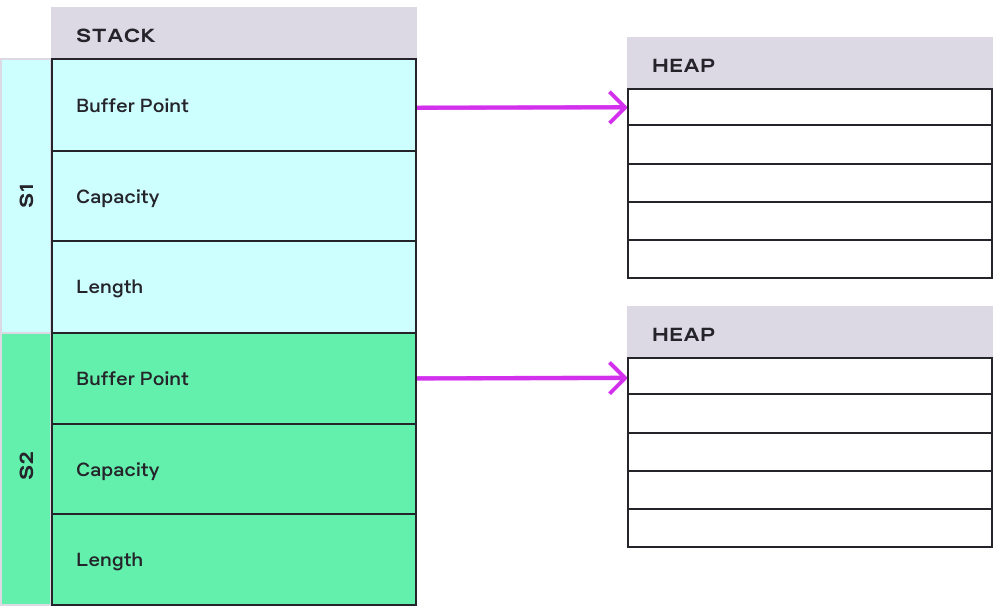

let s = String::from("3327");

let s1 = s.clone();

println!("{}", s); //okAbove, on string s, we call the clone() method, and now both s and s1 are independent. With clone(), we copied the pointer and the heap data.

Each has its heap buffer and is responsible for freeing them.

The ownership model prevents double memory freeing of the same heap buffer. The move can also happen when passing a value as a function argument or returning the value from a function.

In a nutshell, when we assign values, Rust either moves values or copies them.

The ownership model is the same for the passing value to the functions; a variable will move or copy. The return value from the function can also transfer ownership.

The ownership model is the same pattern every time.

Borrowing is a model we use when we want to use a value without transferring ownership. It is used with the borrow operator &.

Example:

let s1 = String::from("3327");

let s2 = &s1;

let s3 = &s1;

println!("{}", s1);

println!("{}", s2);

println!("{}", s3);The above code will compile as we borrow s1 to s2 and s3.

The Rust compiler is very friendly and noteworthy because when you make a mistake, the compiler will give you exact information where you are wrong and information where you can find more about the error, with examples.

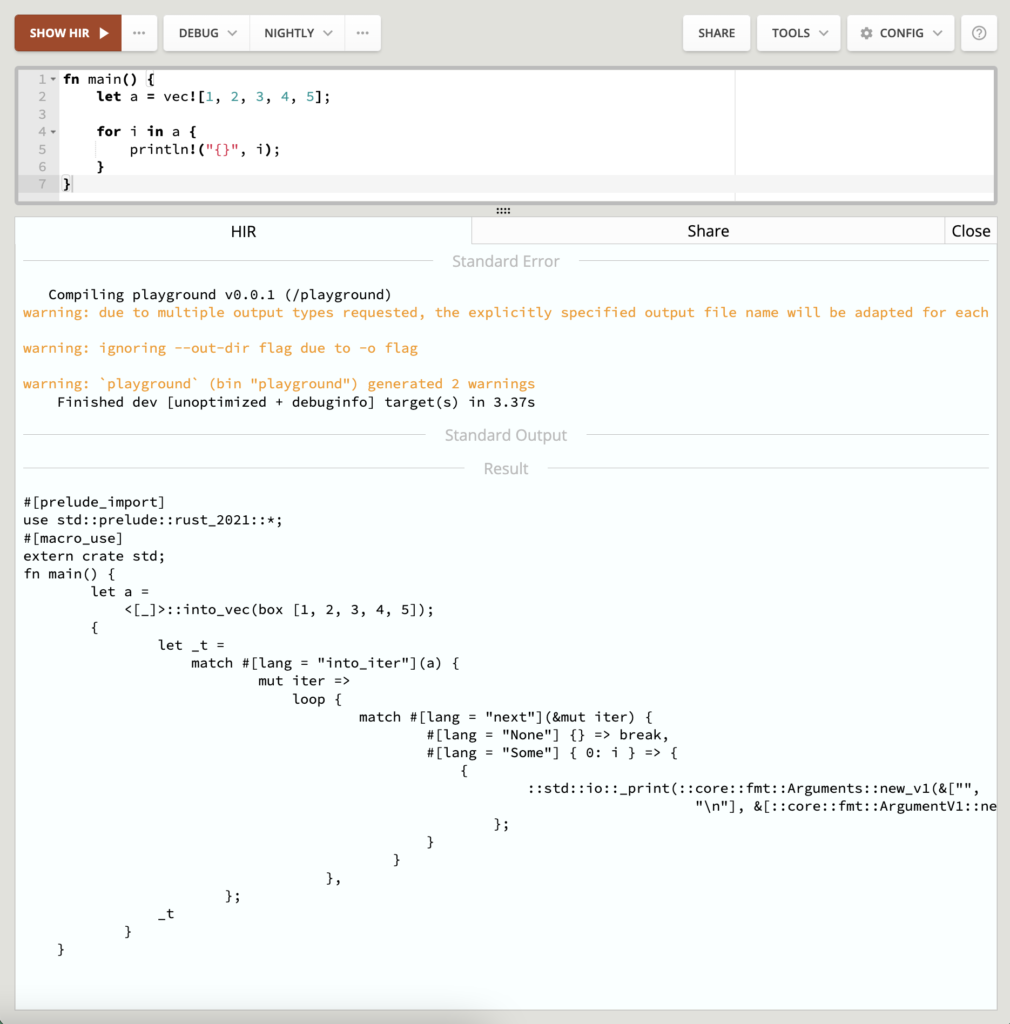

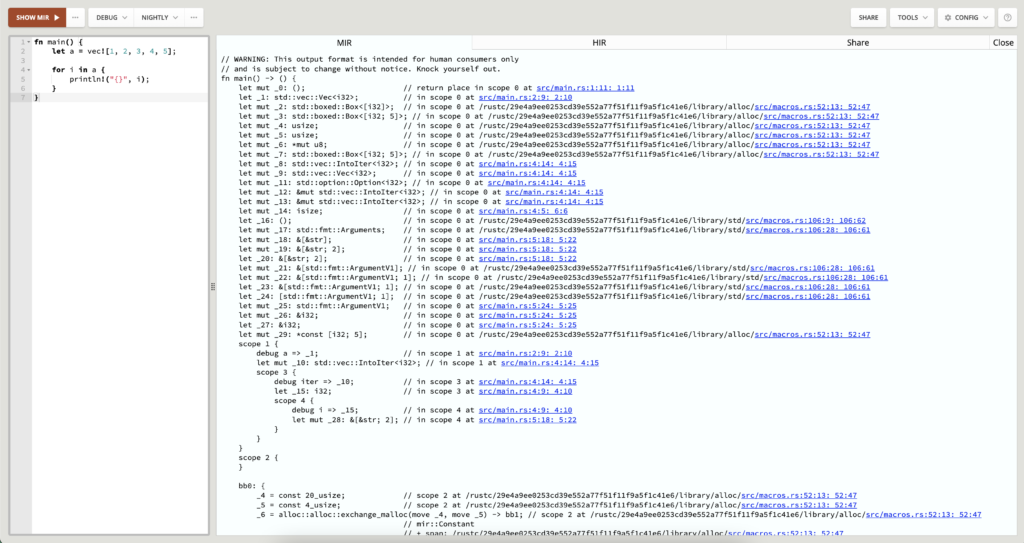

The Rust compiler has two unique steps -> HIR - High-Level Intermediate Representation and MIR - Mid-Level Intermediate Representation.

Inside the HIR step, all macros are desugared, and the code is simplified.

The above code that will print to the standard output is HIR representation. Desugared happens on vec!, println! and loop! Optional are these None and Some. Not human readable.

As part of MIR is a borrow checker, we can see how values move in the memory in the following example.

MIR representation is more complex than HIR, as we have done additional desugaring here. MIR is a control flow graph with some basic blocks with some statements, and the last one is a terminator with a link to where to go next. For each value, we need to have some space in memory. These _1, _2 … _27 are all spaces in memory. When we look at the code from HIR, the line is what we see as a compile error. Now the borrow checker checks how the values are moved and what is valid at a time.

To check how some other examples look behind the scenes check-out -> https://play.rust-lang.org/

We deeply examine how memory management works and how Rust compilers desugar macros, moves values, and optimizes code.

In this post, we covered why Rust is memory safe language through:

This is our first post about Rust, and we hope it makes you fall in love with Rust.

If you have some topics that you want to read about Rust, feel free to leave a comment!

Make sure to follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn as there are more exciting Rust subjects to come!

COMMENTS (0)